What does it mean to be sport specific?

A deeper dive into the validity of "sports specific exercises"

The world of strength and conditioning, performance, and rehabilitation is a saturated market. In major cities (at least in North America), you can’t walk more than 15 minutes without walking by at least a few gyms or clinics. But online? That market somehow finds itself to be even more saturated – with countless pages and people offering coaching or making “content” (I find it hard to say making “educational content” because well, it’s not always so accurate). In this space, one of the biggest advertising points we see is “sport specific training.” Now this is typically targeted to youth athletes, which is why I think this topic bothers me to some degree.

Allow me to walk you through why the concept of sport specific training is in theory fantastic, but just how it falls short of being an accurate term 99% of the time. Some may call this pedantic, but I hope you can appreciate why language, and especially language targeted towards youth athletes, matters.

Part 1: Exploring theories of trying to be sport specific

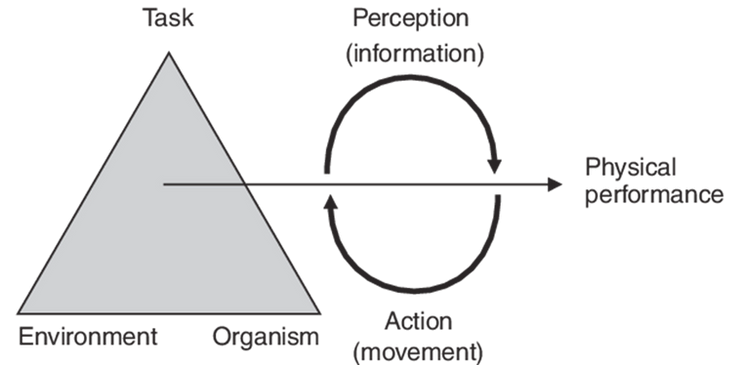

At its core, the idea is simple: sport specific exercises are in theory designed to replicate and therefore improve the exact tasks and demands as seen in the sport. Furthermore, the training is designed to improve game related performance – after all, at a certain point in competitive sports, winning becomes the goal. The problem is that you can’t ever replicate a game in a gym when you’re exercising, there’s just too many external variables missing. In this discussion, I always find myself coming back to Newell’s model of constraints (1), which highlights the different inputs that lead to a movement output:

The model shows that every time we perform a movement, we have to account for the environment, the person performing the movement, the movement (task) itself, and then all the externally available information to the person completing the task. There’s a lot that goes into every single movement, whether we fully appreciate it or not. Immediately, we can see that we can’t replicate a game environment in the gym no matter how hard we may try. We need to be aware that we can never be ultimately sport specific, based entirely on the environmental constraints alone.

Part 2:“But what about if my exercise helps prepare someone for one specific task of playing their sport? That’s sport specific, right?” A motor learning approach.

This is most commonly the response and explanation that we see defending people advertising sport specific training. Sure, we aren’t replicating a game situation with specific movements, but we are training the athlete in the sport specific movements they need. But instead, what if we look at this from a motor learning perspective? I really like how Davids et al (2005) describes motor learning as learning or improving on a skill is the process of acquiring movements patterns based on the constraints placed on each individual (2). An example here is that if you’re training to be a great triple jumper, you’re not going to spend large amounts of time on weighted or resisted static broad jumping. Sure, a standard broad jump can be used as a basic exercise in training, but it can’t be “sport specific” because it lacks major components of the sport itself – meaning that it neither maximizes skill acquisition, nor specifically replicates the triple jump. You’re also not going to put a weighted vest on a triple jumper and ask them to go triple jump, because the specific coordination and movements could be disrupted to the point that all potential benefits could be negated by the change in their movements caused by the weight vest.

In this triple jump example, what would sport specific training be then? Well, actually performing the triple jump, and the various components of the triple jump itself. This can include the action of triple jumping, in addition to a bunch of other technical components to the instruction of triple jump (e.g technical drills designed to improve sprinting mechanics, or each phase of the triple jump). But at the end of the day, anything that describes sport specific training has to be doing the sport you play as close to competition conditions as possible.

Here are a few more examples of what sport specific training actually looks like:

a) Basing your small area games in practice/training to match sprint distance, sprint effort, and total distance covered in soccer (Riboli et al. 2020) (3)

b) Performing a soccer match simulation to work on skills while maintaining game specific pace of play: “Participants were required to perform soccer shooting, passing and dribbling skills throughout two 45 min halves of soccer-specific activity separated by a 15-min passive recovery period (half-time)” (Russel et al. 2011) (4)

These two studies nicely show examples of what “sport specific training” is. Purposefully and scientifically designed practice conditions, that aim to improve sport related motor patterns, while closely mimicking the environment and conditions of game play.

Part 3: “So what are these sport specific exercises doing then anyways?”

If we take the American College of Sports Medicine (5) five components of physical fitness – most exercises work towards one or more of the following: body composition, muscular strength (we’re going to toss power/force production in here), muscular endurance, flexibility, and cardiorespiratory fitness. While I don’t think this really covers it all, it does highlight to a good enough degree that exercises are designed to improve different levels of fitness which then may improve sports related performance.

One study that articulates this concept nicely is by Loturco et al (2019) (6). They took 61 athletes (including 15 Olympians) from four different sports – and assessed them by performing half squats, jump squats, and sprint tests. The goal was to see if force production via the half squat and jump squat was related to sprint performance. Unsurprisingly, there was impressively high correlations between the power outputs from the half squat and the jump squat and the 60m sprint (-0.91, and -0.90 respectfully).

“But Ben, that’s association science, show me some longitudinal data” you say. Well, I’d love to so here you go! In a study by Deprez et al. (2015), the authors followed 55 Belgian soccer players from the ages of 7-20. What they found is that once athletes pass puberty, “the only longitudinal predictor for explosive leg power, next to chronological age was fat-free mass (7).” This suggests the importance of muscle in the development of explosive power, especially as youth athletes become young adults. From this, it should be evident that our goal/outcome for a lot of our exercise prescription is muscular development and strength.

Above all else, there’s one study that I believe really highlights why this discussion around sports specific training misses the mark in a bunch of different ways. In 2013, Jacobson and colleagues published seven years of longitudinal training data looking at college American Football athletes (8). Measurements included, 1 rep max bench press, squat, and power clean, as well as vertical jump, and 40-yard sprint. What the authors found is that while all the subjects in the study improved their strength and power (as measured by the exercises listed above), the improvements in athletes’ speed averaged to be between 1.7-2.7%. The authors concluded that while training can improve strength output and muscular endurance, genetics may play a significant role in speed and power when we consider that every athlete had the same training opportunities. One potential argument behind this is that these athletes were already extremely close to their peak abilities, and that any changes they could possibly get are already very small. I find this incredibly fascinating, that athletes given fairly optimal conditions and training saw very small improvements in practical qualities related to their sport. This doesn’t mean that strength isn’t valuable – it certainly is for many aspects of American football. It just likely means that to improve in an aspect of a sport, specificity truly matters.

To add to this one example, NFL combine scores don’t predict NFL performance except for maybe the 40-yard dash showing some predictive value for running backs (9). This means that once people are of relatively equal general performance levels (read: they’re all strong, and they’ve all trained a lot), these isolated tasks measurements don’t always translate to practical applications. Remember how early on I said the only thing sport specific is doing the sport?

Part 4: Wrapping it all up

Looking at this conversation from a lot of different angles shows that improvements in sport largely and likely comes from a combination of improvements in fitness categories, and skill acquisition and development within the sport itself. Based on the available data we have, it seems clear to me that we should be maximizing our time away from sport optimizing these areas of fitness, while spending our time in sport training focusing on the required motor patterns needed to become a master of that sport. Truthfully and simply, it’s inefficient to try and blend the two together.

A final example: If someone is doing lunges on a bosu ball, you’re not maximizing ANY of the benefits that come from the lunge. You end up limiting the weight you can do, resulting in not maximizing muscular strength or power benefits that may come from doing lunges in the first place, all the while not maximizing benefits from stability and balance training. Last I checked, no sport plays or interacts with bosu balls – meaning that if the argument behind the bosu ball is to work on stability and balance, there is limited transferability to any of the sports or activities you play. Unless you’re a professional bosu ball athlete, in which case I apologize, and you are right.

At the end of the day, sport specific training is more marketing than science. There is a wide variety of options to improve your fitness levels outside of the sport you play, but please remember to evaluate why you’re training in the first place. If it is to improve your strength or your power output, then select the appropriate exercises that can help you with that. But most importantly, whether you’re a coach, a parent, or the athlete yourself, please don’t follow Jameis’ Winston’s approach of “sport specific exercises”.

References:

1) Newell K. Constraints on the development of coordination. Motor development in children: Aspects of coordination and control. 1986.

2) Davids K, Chow JY, Shuttleworth R. A Constraints-based Framework for Nonlinear Pedagogy in Physical Education1. New Zealand Physical Educator. 2005 Aug 1;38(1):17.

3) Riboli A, Coratella G, Rampichini S, Cé E, Esposito F. Area per player in small-sided games to replicate the external load and estimated physiological match demands in elite soccer players. PloS one. 2020 Sep 23;15(9):e0229194.

4) Russell M, Rees G, Benton D, Kingsley M. An exercise protocol that replicates soccer match-play. International journal of sports medicine. 2011 Jul;32(07):511-8.

5) American College of Sports Medicine. (2013). ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

6) Loturco I, Suchomel T, Bishop C, Kobal R, Pereira LA, McGuigan M. One-repetition-maximum measures or maximum bar-power output: Which is more related to sport performance?. International journal of sports physiology and performance. 2019 Jan 1;14(1):33-7.

7) Deprez D, Valente-Dos-Santos J, Coelho-e-Silva MJ, Lenoir M, Philippaerts R, Vaeyens R. Longitudinal development of explosive leg power from childhood to adulthood in soccer players. International journal of sports medicine. 2015 Jul;36(08):672-9.

8) Jacobson BH, Conchola EG, Glass RG, Thompson BJ. Longitudinal morphological and performance profiles for American, NCAA Division I football players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2013 Sep 1;27(9):2347-54.

9) Kuzmits FE, Adams AJ. The NFL combine: does it predict performance in the National Football League?. The Journal of strength & conditioning research. 2008 Nov 1;22(6):1721-7.

I don't know if you interact on the comments but I enjoyed reading!

I agree to be sport specific means to work more at the specific sport in hand. However, do you think that developing strength, power, speed, endurance, overall fitness, etc as an accessory that does not overly impact sport specific training, would be beneficial?

I appreciate the exercises to complete these tasks can be taxing but for example during pre-season training would it be preferable to work on sport specific (triple jumps for example) or developing strength/decreasing fat free mass, etc?

PS the balance exercises are ridiculous but if a bosu ball comes flying onto a rugby pitch a lot of athletes will be prepared haha